The post Gators back Gators in new artificial intelligence investment – Mainstreet Daily News Gainesville first appeared on JOSSICA – The Journal of the Open Source Strategic Intelligence and Counterintelligence Analysis.

Bryan Kohberger: Where Is The Suspected Idaho Murders Killer Now? ComingSoon.net

The post Bryan Kohberger: Where Is The Suspected Idaho Murders Killer Now? – ComingSoon.net first appeared on Idaho Murders – The News And Times.

UNMC lab accredited to apply genetic genealogy to cold cases Omaha World-Herald

The post UNMC lab accredited to apply genetic genealogy to cold cases – Omaha World-Herald first appeared on Idaho Murders – The News And Times.

This article is part of The D.C. Brief, TIME’s politics newsletter. Sign up here to get stories like this sent to your inbox.

When the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade two years ago, Kelley Robinson was running the political shop at Planned Parenthood. Like so many abortion advocates and activists, she had seen the moment looming insidiously for so long. Even still, its arrival felt like both a personal and professional thwacking. It was a moment meriting despondency, but even taking the time for that seemed like an indulgence.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

“Up until Roe was overturned—even after the leak that they planned to overturn Roe came out—we polled folks across the country and they still did not believe it was true,” Robinson tells me. “They just would not believe that the Supreme Court in our lifetime would actually overturn such a fundamental right that had been the law of the land for over 40 years.”

Robinson is now president of the Human Rights Campaign, the nation’s largest LGBTQ civil rights organization, and fears she’s watching the same slow-moving car crash all over again. The most glaring sign of many came about on the day Roe fell.

“In Clarence Thomas’ dissent, he says the quiet part out loud: next they are coming for Windsor and Obergefell and Lawrence,” she says, citing three rulings that unlocked a national right to same-sex marriage.

Put another way: the foundational underpinning of LGBTQ rights is up there on conservatives’ list of targets, and they’re not exactly announcing it in a whisper.

Before 2015, whether a same-sex couple could marry varied by state. With its 5-4 decision in Obergefell v. Hodges, the Supreme Court extended the federal right to marry to same-sex couples. It was a reflection of how much the country’s views of same-sex relationships had already shifted, and would continue to do so in the years that followed. But while the polls have moved one way, the composition of the Court has shifted in the other direction. If Roe could fall after 49 years in a 6-3 ruling in the Dobbs v. Jackson case, there’s no reason to think Obergefell is any safer after less than a decade in action.

It’s the legal earthquake that people like the lawyers at the Human Rights Campaign’s headquarters in Dupont Circle argue could come as soon as next year. Yet even some of those who worked for years to help secure a right now enjoyed by hundreds of thousands of couples refuse to believe it could be taken away. Same-sex marriage, they argue, is too popular, too engrained and accepted in American society. The Court wouldn’t dare.

Or would they? A clear-eyed examination of the political and legal landscape makes it impossible to dismiss out of hand. The threats are as real now to Obergefell as they were to Roe, whose durability was largely taken as an article of faith until it was too late. The legal breadcrumbs are not difficult to find for those looking hard enough. Justice Samuel Alito in particular has been sprinkling swipes at Obergefell in concurrences and dissents since 2020. And then there are the smattering of cases—mostly to do with trans rights—working their way through courts in red states. Any one of those reaching the nation’s highest court could give the 6-3 conservative majority a chance to undermine Obergefell, or wipe it out entirely, and with it, the other rulings that cite it as precedent. And it must be noted: only two Justices who voted in favor of Obergefell remain on the bench—Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan.

Here, you may be hitting a bump. Didn’t Congress fix this? They’d like to think so. But there are enormous shortcomings in the 2022 Respect For Marriage Act that ordered states to respect marriage licenses, adoption orders, and divorce decrees issued in other states. It also gave a buffer to earlier rulings that allowed interracial couples to wed.

But it did not codify Obergefell. Instead, it scrapped the 1996 Defense of Marriage Act, which would have snapped back into effect if the Court were to spike Obergefell. The law has so many loopholes that even the conservative Mormon church endorsed it, as its leaders understood that it might someday empower states like Utah, which roughly 133,000 LGBT residents call home, to tell gay couples to go elsewhere to get a marriage license.

“People think that marriage equality is a fait accompli,” says Rebecca Buckwalter-Poza, a former spokeswoman for the Democratic National Committee and Yale Law graduate who is on the board of LPAC, which raises money to help lesbians and their allies win elections. “They think that not just because of Obergefell but because of the Respect for Marriage Act. They’re wrong—dangerously wrong.”

If the red-blue divide in this country that emerged for abortion rights is any guide, we would likely to see a similar geographical split on access to same-sex marriage in a post-Obergefell legal environment. But that would just be the start. Many Republican-controlled states would likely take steps to not just ditch marriage licenses for same-sex couples, but also ignore scores of anti-discrimination rules and regulations that federal agencies promulgated based on rights some say are justified through Obergefell. The ripple effects would be massive and, for potentially millions of members of the LGBTQ community, heart-wrenching.

It’s why Robinson is among those pushing Democrats to make the case more forcefully that same-sex marriage, and LGBTQ rights more broadly, are on the ballot just as much as abortion.

“What we are seeing is similar to what we saw in the abortion fight, right?” says Robinson. “They didn’t go after Roe first. They came at us with death by a thousand cuts, but always with the same goal of undermining abortion access. That’s what’s happening here.”

Here, it’s worth another pause and a reminder. Public opinion—and law—has changed so rapidly during the last decade on LGBTQ rights that it can be easy to forget that the legal scaffolding upholding much of it is disturbingly fragile. The big breakthrough came in a 2013 ruling about inheritance laws, United States v. Windsor. Later that year came Hollingsworth v. Perry and Prop 8, which restored same-sex marriage in California, yielding a neck-breaking Obergefell in 2015. It was a joyous march for LGBTQ community and their allies, but activists were warning me only months later to not be fooled into thinking a Golden Age of Gay had arrived.

They were right. Onward came the Bathroom Bills. And bans on transgender athletes. And potential child-separation laws in places like Texas that allow the state to take trans children away from their parents. For those who may think trans rights are a separate issue from broadly accepted gay rights like same-sex marriage, you are missing how nearly all of these rights are anchored on an LBGTQ-inclusive reading of the 14th Amendment’s provision that says all Americans have the same protections. For most of the current era, race and sex were considered parts of an American’s identity, while their sexuality and gender identity were not.

To be sure, it’s not clear if the votes are there at the moment to end the constitutional right to same-sex marriage. But at least two Justices, Alito and Thomas, appear to be itching to overturn Obergefell. And it’s immensely clear that they are fairly immune to public opinion, political pressure, or demographics.

In 2020, when presented an appeal from a Kentucky county clerk who refused to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples after Obergefell, the duo said that the case record wasn’t the best version of a precedent-reversing action and indicated that they’d wait for a better one. “Until then, Obergefell will continue to have ruinous consequences for religious liberty,” Alito and Thomas wrote.

A year later, a unanimous Supreme Court ruled that Philadelphia’s Catholic Social Services could refuse to work with same-sex couples on foster care in defiance of the city’s non-discrimination laws. But Alito issued a concurring opinion arguing for a deeper review of precedent that does not require states to set aside laws to accommodate religious beliefs. Alito has long argued that religious beliefs can trump civil laws. “As long as it remains on the books, it threatens a fundamental freedom,” Alito wrote in the Philadelphia case.

All of which has LGBTQ court-watchers nervous on any number of cases that are winding—albeit some more slowly than others—toward Washington.

“The distillation of the crisis we face to whether Obergefell falls is apt and, in a way, an inversion of a familiar problem: the conflation of marriage equality with what it takes to protect LGBTQ+ people in day-to-day life,” says Buckwalter-Poza. “We didn’t win civil rights for queer and trans folks across the board just by winning Obergefell, but we absolutely do stand to lose everything if we lose Obergefell.”

No massive, sweeping anti-LGBTQ case is in the offing this term, which ends this summer, according to those who are tracking every utterance from the Court. But narrower ones are inching forward and could be consequential.

The most proximate seems to be a case coming out of Tennessee, where the state passed a ban on doctors providing gender-affirming surgeries, administrating puberty blocking drugs or prescribing hormone therapies on minors. A Memphis doctor and three families are trying to keep the minors enrolled in treatment that could be ordered to be ended by March 31. An appeals court upheld the state’s case against the trans teens; the Supreme Court hasn’t decided if it would join this state-by-state anti-transcare bingo landscape.

Other cases potentially coming from Florida and Utah stem from public-accommodation needs, including school bathrooms and locker rooms. (Such laws require visitors of certain public buildings use facilities that match the gender on birth certificates that were issued before the families left the hospitals.)

But federal judges in Richmond, Va. seemed sympathetic last year to a transgender girl from West Virginia looking to compete on the girls’ track team in her middle school, but blocked by state law. (The court has yet to rule on the case.)

And much of Washington is awaiting a potential Title IX case that more than a dozen Republican attorneys general are bringing against the Education Department’s proposal that simultaneously goes too far and not far enough in protecting transgender student athletes. Those AGs say the proposal—which would allow schools and colleges to define sport-by-sport rules for athletes—guts the very core of Title IX, which is best known for boosting opportunities for women to participate in college sports. LGBTQ lawyers, meanwhile, maintain that the framework creates an unequal system, where some team buses will be inclusive and others will be allowed to be harbors of anti-trans rhetoric.

Not everyone is convinced that this legal environment means Obergefell is at risk.

“It’s very easy to see where one or two votes would come from on the Court for this based on Thomas’ opinions and Alito’s,” says Sasha Issenberg, a journalist whose study of same-sex marriage politics and law, The Engagement, is a must-read volume about the era. “Showing me where the third, fourth, or fifth vote is becomes very difficult with this Court.”

Yet even a skeptic like Issenberg agrees that the concern isn’t completely unfounded.

“The fact is there are a lot of other terrible things that Republicans are doing to members of the LGBTQ community now, and you don’t have to reach that far for speculative stuff,” he says.

For Robinson, this is all feeling awfully familiar. She spent a good part of her career fighting liberal complacency about the sturdiness of a popular constitutional right, only to see the Dobbs decision burn it to the ground.

She and many of her colleagues watched as the groundwork was being laid decades earlier with President George W. Bush’s addition of John Roberts and Samuel Alito to the Supreme Court. Those were no accidental nominees, but the building blocks to eventually overturning Roe. And Bush was hardly alone in his Republican Party. Even someone seen as a moderate maverick like Sen. John McCain, the GOP’s presidential nominee in 2008, made no secret of his desire to nominate Justices who had already ruled favorably toward abortion limits.

Yet so comfortable were Democrats with Roe’s resiliency that they did not panic when, just five months into his presidency, Barack Obama went to Notre Dame to deliver a commencement address that spoke of working to reduce the number of abortions in the nation. Throughout his eight years in office, Obama’s faith-based advisers spent considerable time looking for areas of mutual agreement, only to find zero-sum partisanship motivated voters more than compromise.

In 2016, Donald Trump did little to conceal his overt pandering to the anti-abortion rights crowd. His defeat over Hillary Clinton came about in part because the majority of Americans who supported access to abortion didn’t believe Roe could ever be overturned.

Nonetheless, there were still plenty of abortion rights supporters concerned about restrictions being pushed in statehouses and in Congress to fuel a massive expansion of Planned Parenthood footprint in the political space. Robinson witnessed the group’s supporter roster grow from 6.5 million to 18 million during her on-and-off, decade-long tenure at the group’s political arm.

Like 2016, the 2020 presidential campaign never hinged on abortion. The economy drew the most important billing for 35% of Americans and 20% cited racial inequality. Still, Robinson helmed a $45 million electoral machine for Planned Parenthood Action Fund that year.

Then came Dobbs, and what had been an afterthought in 2008—abortion access—rocketed in 2022 to being second only to inflation as a deciding factor in people’s vote. A full 27% of all voters pointed to abortion as their top deciding factor, and Democrats were about three-times as motivated on the issue than Republicans.

For decades, presidential candidates often spoke about the Supreme Court in the context of Roe. Now Obergefell might be a better barometer. Even if a majority of justices aren’t ready to rule that same-sex marriage is no longer protected under the 14th amendment, whoever is sitting in the Oval Office over the next four years could find themselves replacing enough members to shift that dynamic fairly quickly.

Yet strategists in both parties have advised campaigns against elevating LGBTQ rights too highly on their agenda, saying abortion is the more animating tool, both for activists and donors.

That kind of thinking ignores how many voters have a vested interest in preserving Obergefell and other LGBTQ gains. New data released Wednesday from Gallup shows 7.6% of Americans identify as LGBTQ—twice the level as when Gallup first asked the question in 2012. Among GenZ—folks who were ages 18 to 26 when reached by Gallup—that number is 22.3%. And Millennials in the next grouping above them and up to age 42, the figure stands at 9.8%.

Put another way, one-third of LGBTQ Americans are under the age of 43 and stand to be voting for many, many elections to come.

On top of this, an average of 2,200 LGBTQ individuals turn 18 every single day.

President Joe Biden clearly gets it. As he addressed a packed lawn of Washington’s LGBTQ insiders gathered in December of 2022 to watch him sign the Respect For Marriage Act, he drew a direct line from Roe to Obergefell.

“An extreme Supreme Court has stripped away the right important to millions of Americans that existed for half a century. [With] the Dobbs decision, the Court’s extreme conservative majority overturned Roe v. Wade and the right to choose,” Biden said, specifically noting Thomas’ opinion that cited precedent on contraception, sexual conduct, and marriage. Biden’s re-election campaign has made the Court’s move on abortion central to his pitch to on-the-fence voters, and he often adds in an occasional reference to LGBTQ rights for good measure. He specifically made a nod to transgender rights in his State of the Union last week: “I have your back.”

For his part, Trump has been more vague when it comes to LGBTQ rights. At his 2016 nominating convention, billionaire Peter Thiel became the first openly gay speaker at a GOP convention to acknowledge their sexual orientation. But as President, Trump also put in place three Supreme Court Justices—among the 234 federal judges confirmed on his watch—who have been transparently hostile to LGBTQ rights. A Trump campaign spokesman did not return a query about the former President’s position these days.

While the fall of Roe is reality, and Obergefell’s remains theoretical, both issues warrant better attention by the candidates and voters. “This isn’t just some sort of fantasy. This could actually be our reality unless we do something,” says Robinson. “It’s why 2024 matters so much.”

Make sense of what matters in Washington. Sign up for the D.C. Brief newsletter.

The post The Fight for Same-Sex Marriage Isn’t Over. Far From It. first appeared on The News And Times.

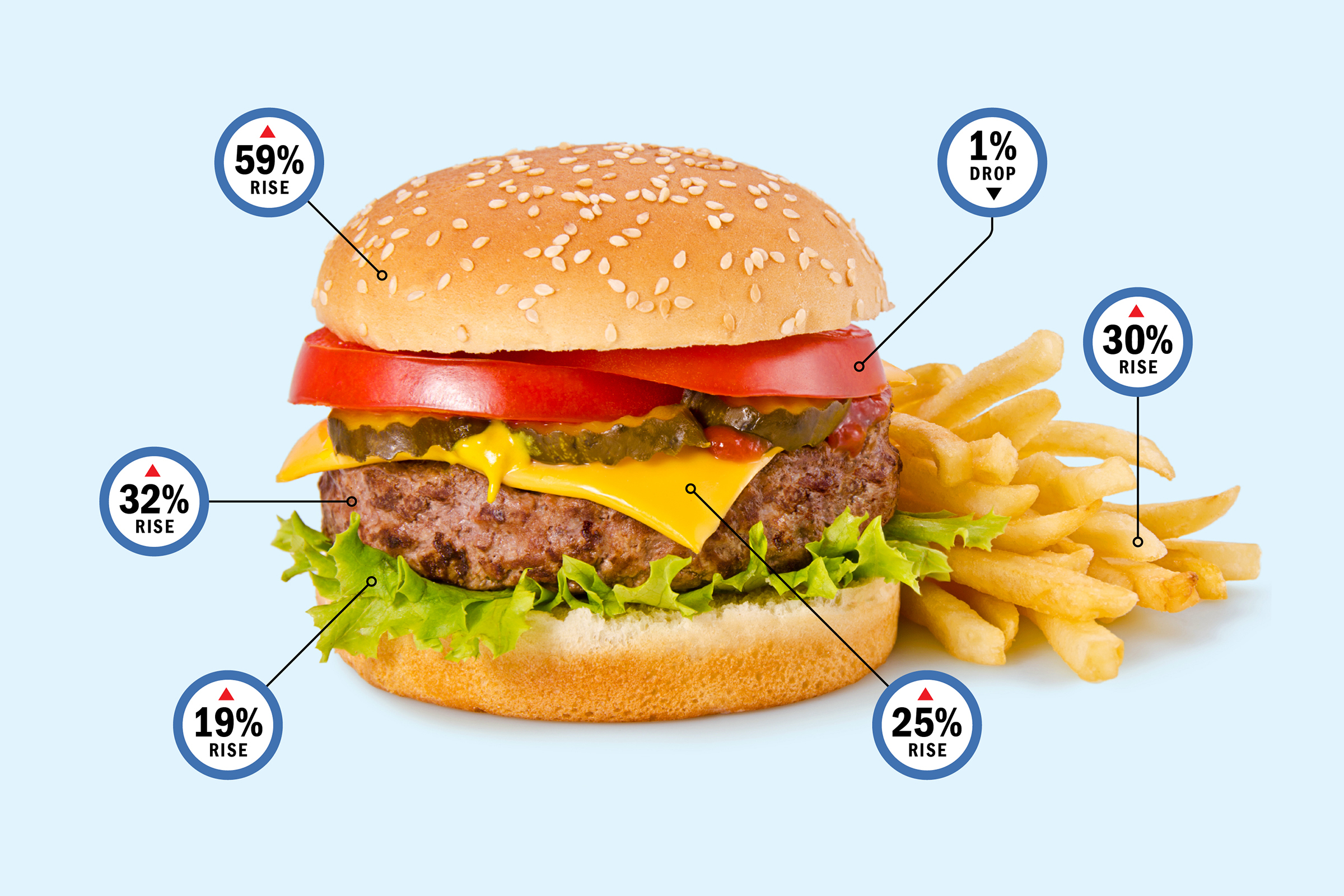

Why a Burger Costs More Now

The good news about inflation in recent months is that it’s slowing, but that probably doesn’t matter much to the American consumer; slowing inflation still means that prices are rising. The cost of groceries ticked up just 0.3% from the previous month in January, but has grown 28% since January 2019. No wonder Americans still get sticker shock when they look at their grocery bills.

It may seem contrary that prices are still rising when so many of the events that kicked off the high inflation of recent years—the COVID-19 pandemic, the resulting supply chain headaches, the war in Ukraine—started years ago. But there are dozens of different factors that go into food inflation.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

To explain these factors, TIME picked a meal that might be typically consumed by an American household—a cheeseburger and fries—and looked at what’s driving prices higher for different ingredients. We found that the cost of ingredients for a cheeseburger and fries—$4.69—is roughly a dollar more than in 2019, though just pennies from a year ago.

Wells Fargo chief agricultural economist Michael Swanson explains the factors driving up prices bite by bite:

White bread: Up 59% since 2019

Bread is one of the items that jumped the most in price since the beginning of the pandemic. The dollar figure isn’t much—a pound of white bread costs $2.03 now, up from $1.27 in January 2019, according to government data. What happened? Bread was really cheap for a long time, Swanson says. The price was so low that it essentially fell from 2014 to 2019, as cheap wheat and robust bakery competition forced bread makers to lower prices. The bread business was so tough that many bakeries went out of business or consolidated.

Prices started rising at the beginning of the pandemic, but really jumped in early 2022 after Russia invaded Ukraine and the price of wheat spiked. The price of wheat has since cratered, but the Russian war gave producers an excuse to increase prices. For years, bakeries really needed the price of bread to go up to cover their labor, energy, and transportation costs, and finally, they had the opportunity. “Once the dam broke, it was going to be quite awhile for the inflation to go back down,” Swanson says.

Processed cheese: Up 25% since 2019.

In 2022, the price of milk was too low for farmers to make money, so they started culling their herds; cheese buyers, anticipating that there would be a shortage of cheese, started “leapfrogging each other to get supplies purchased,” Swanson says. That drove cheese prices up to their peak in April 2022. The same thing may be happening now, he says; a recent milk production report showed heavy signs of culling.

Even if the price of cheese drops on commodities markets, it can take awhile for consumers to feel the difference. When cheese prices skyrocketed in 2022, retailers couldn’t raise prices that much, Swanson says. So when cheese prices fell back down, retailers tried to recover what they had lost. The price of processed cheese is still 25% above what it was in January 2019.

Ground beef: Up 32% since 2019

In the beginning of 2024, there were only 87.2 million cattle and calves in the United States. That may seem like a lot of cows—roughly one for every four people in the U.S., but that number actually represents the lowest inventory since 1951. Fewer cows means higher prices for the ones that are getting sold and turned into meat.

U.S. herds are at such low levels primarily because of drought and high supply costs. In the last four years, as drought plagued Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, and other cattle-raising regions, farmers found that it was costing a lot of money to feed their cows. They started selling them—and, unusually, they also sold female cows, who would typically have been held back for breeding, according to economists from the American Farm Bureau Federation.

Now, El Nino has brought moisture to much of the U.S., and farmers are trying to rebuild their herds. But doing so will be expensive, keeping the cost of beef high. While the U.S. had a record corn crop in 2023 and prices of feed are falling, some farmers are holding back cows they otherwise would have sold in order to rebuild their herds. With higher interest rates for borrowing and more expensive cows, beef prices aren’t likely going anywhere soon. In February, economists from the American Farm Bureau Federation predicted that 2024 would be characterized by record-high beef prices in the grocery store.

Tomatoes: Down 1% from 2019

One of the only foods that have not experienced major price increases over the past four years. That’s in part because they were already expensive compared to other fruits and vegetables. But tomato prices are also affected by trade rules; ever since 2013, U.S. and Mexican producers have essentially agreed to set the price of tomatoes so one country’s farmers don’t have an advantage over another.

Potatoes: Up 30% from 2019

Potato crops in 2021 and 2022 were severely affected by drought and wildfire smoke, reducing yields. With fewer potatoes in the U.S. and abroad, prices jumped. In 2023, though, U.S. potato production increased for the first time in seven years, which should temper prices.

Romaine Lettuce: Up 19% from 2019

An insect-born virus destroyed huge swaths of lettuce crops in California in 2022, causing costs to spike. The price has fallen since then, but labor and transportation costs are still higher than in 2019, which means suppliers aren’t rushing to bring down prices further.

You Won’t Save Money Dining Out

Your restaurant burger is probably going to get more expensive, too, as wages continue to rise in a competitive job market. “Across the board, everything is just up,” says Brian Arnoff, the co-owner of Meyer’s Old Dutch, a hamburger restaurant in Beacon, N.Y., his restaurant has done two pricing increases since the pandemic, its burger now costs $16, up from $13 in 2019.

For restaurants, though, labor accounts for much of the increased cost of food. Meyer’s Old Dutch can’t even get applicants to come to interviews unless he offers $18 an hour, significantly higher than the state minimum wage of $15 an hour. Wages across his business have climbed as he tries to retain talent; cooks who made $18 an hour in 2019 are now starting at $20. Until the pandemic, Arnoff says, the cost of food and other supplies surpassed the cost of labor. Now, he spends more on labor than on ingredients.

The post Why a Burger Costs More Now first appeared on The News And Times.